August 23, 2022

By: Lynn Vaccaro, Great Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve

How can we protect our shorelines from erosion and rising seas while preserving the ecological benefits of a natural shoreline? That’s the question the Great Bay Living Shoreline project has been tackling over the past year, and now we can see the newly generated designs and ideas for four diverse Great Bay sites.

Beginning in the fall of 2021, 24 professional engineers, wetland scientists, and landscape architects joined an eight-month design and training program organized by a team of agency and university partners. Participants were organized into four Design Teams and each team was asked to develop a suggested living shoreline design for a specific site around Great Bay. (Read more about how the four sites were chosen here). UNH scientists and project partners supported the Design Teams through several workshops, field assessments, and a facilitated design process.

After several rounds of review and modifications, the designs were presented in a final workshop attended by more than 140 people (See: video recordings of the final workshop). The Design Teams’ presentations, reports and design drawings are now available on the project webpage.

Shoreline solutions for four sites

Many factors contribute to shoreline erosion – including runoff from homes and parking lots, foot traffic and mowing which damage natural vegetation, rising seas and strong waves – and these factors need to be considered when assessing a site. Each Design Team worked to design a living shoreline that addressed the unique needs of their landowner and the ecological and social context of the site. The suggested designs for four project sites illustrate how living shoreline concepts can be applied to address different issues and needs in distinct settings.

|

|

The suggested design for Schanda Park in Newmarket recommends creating rain gardens around a parking lot and replacing a failing rock wall with a narrow constructed marsh as a greener way to stabilize the shoreline of a popular downtown park (learn more).

|

|

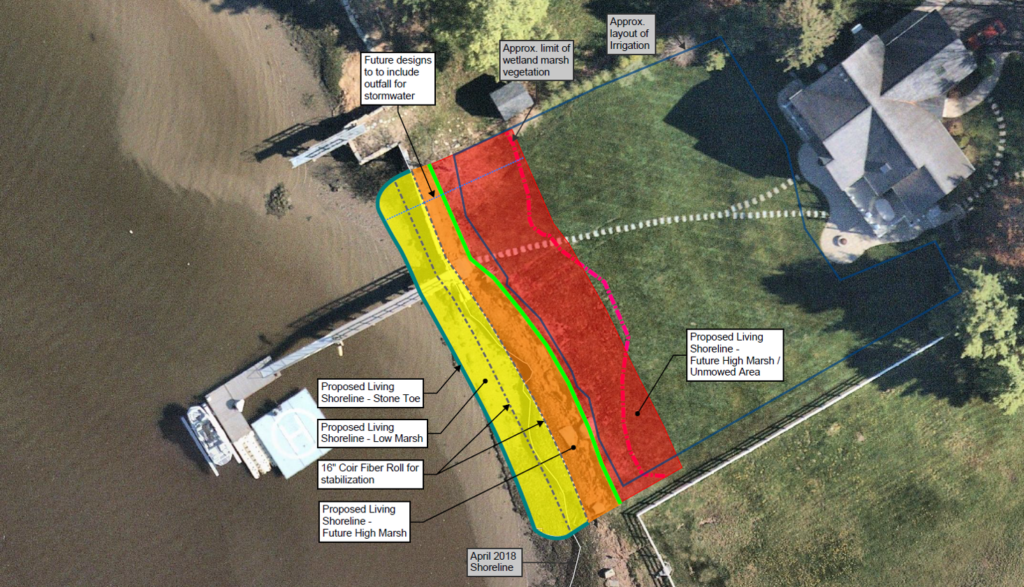

The design for a home on Spur Road in Dover illustrates how the techniques used at Wagon Hill Farm could be used for a small property. Recommendations include adding rock to stabilize the eroding shoreline edge, planting marsh grasses and limiting mowing along the shoreline (learn more).

|

|

At Chapman’s Landing in Stratham, the Design Team discovered that erosion rates were relatively low, so they recommended that the landowner continue to monitor and only intervene if conditions change. In addition, a boardwalk was proposed to reduce the impact of foot traffic on the salt marsh (learn more).

|

|

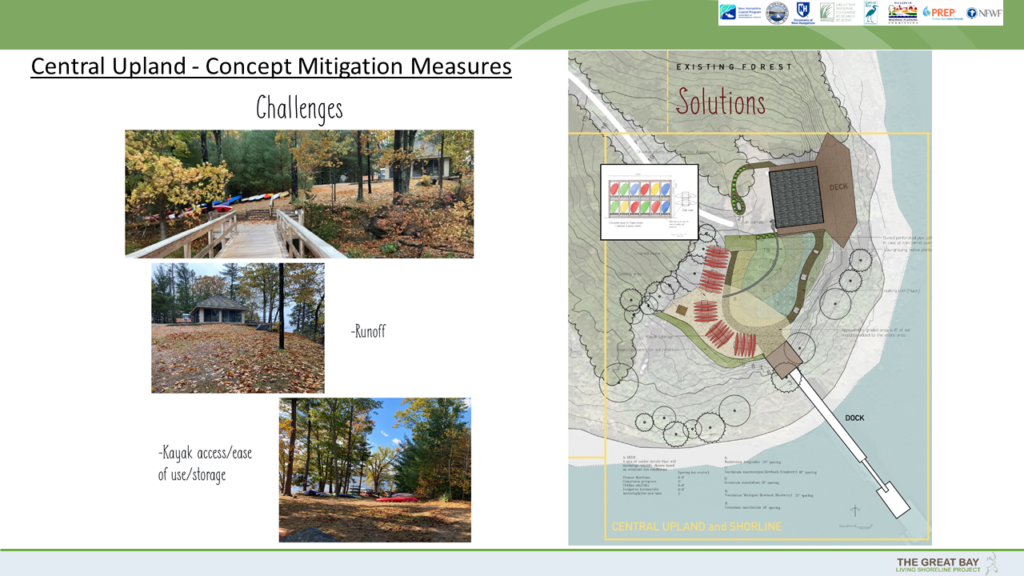

To address shoreline erosion concerns at Moody Point Community in Newmarket, the Design Team proposed strategies for reducing stormwater runoff, managing foot traffic and improving a kayak launch, as well as using fabric encapsulated soil lifts to stabilize the steep shoreline (learn more).

Each of these suggested designs are available on the project webpage, but they are not final, have not been granted regulatory approval, and are insufficient for construction. Advancing the design concepts will likely require assistance from an environmental consulting firm to finalize site assessment, engineering designs, permit applications, and construction specifications.

Identifying barriers

Although living shoreline approaches are broadly supported by regulators and natural resource professionals, there are relatively few examples of these techniques being used in New Hampshire. The Great Bay Living Shoreline Project was an important opportunity to identify some of the barriers to broader adoption. By talking with the consultants, landowners and regulators participating in the project, the project team identified the following next steps to address challenges and further promote living shoreline approaches:

Improve Policy:

- Bring together agencies to better align regulations and funding

- Create opportunities for more collaboration among consultants, landowners, regulators and researchers

Improve Project Planning and Design Capacity:

- Develop locally relevant technical design resources including best practices, case studies, and cost/ benefit analyses for living shorelines

- Offer training that further explores ecological design engineering concepts

Increase Landowner Interest:

- Identify ways to make design, engineering, construction and plant purchasing cost effective for residential properties.

- Generate more landowner interest in living shorelines through incentives, outreach, demonstration sites, and other funding sources.

In addition to promoting the individual site designs, the project team developed a comprehensive summary of the project approach and broader lessons learned to enable others to expand on this project. See: Road Map Report. Project partners are eager to continue working with natural resource professionals and landowners to promote resilient shoreline strategies.

|

|

The Great Bay Living Shorelines Project is supported by a grant from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation with matching support from the Town of Durham. The project is led by the New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services Coastal Program, the University of New Hampshire, the Great Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve, the Piscataqua Region Estuaries Partnership, the Great Bay Stewards, and the Strafford Regional Planning Commission.

Questions? Contact Aidan Barry, Coastal Resilience & Habitat Specialist, NHDES Coastal Program, aidan.t.barry@des.nh.gov